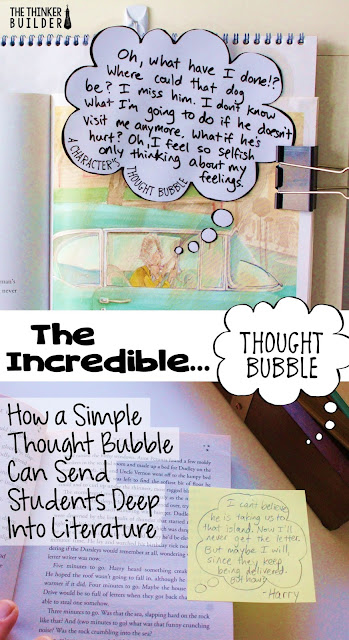

How a Simple THOUGHT BUBBLE Can Send Students Deep into Literature

When you read, do you ever think about what a character is thinking?

This is not a trick question.

You do, right? Of course you do. You may not even realize the extent to which you do it.

If we slow down the process (like, The Matrix slow-motion slow), an experienced, engaged reader gives a lot of consideration to a character's thoughts.

Let me give you an example.

Let's say I'm reading Harry Potter (the first one) and I'm in the part towards the beginning when Harry's Uncle Vernon refuses to allow Harry to open any of the letters from Hogwarts, and goes to great lengths to keep them from Harry, even moving the whole family to a dreary rock of an island in the middle of the sea.

So what do I think Harry is thinking?

I think Harry must be streaming several lines of thought. He detests living with his Aunt and Uncle and Dudley but has become rather hopeless that his situation will improve, and then along comes a letter addressed to him. He allows himself a glimmer of hope, but then his Uncle destroys the letter as well as the subsequent letters that follow. Harry is probably coming to terms with the idea that his Uncle will go to any length to keep him from opening the letter. Which is a bummer.

But.

But, he also has to be thinking about the logic that whatever is inside those letters must be pretty significant if his Uncle is willing to move the family to the middle of nowhere in the middle of a storm just to keep more letters from being delivered. Which is intriguing.

And Harry also must have given some thought to the persistence of whomever is sending the letters. If they've continued to mail him dozens of letters, hundreds even, why wouldn't they continue until he has received one? Which is promising.

I want them to be able to use a character's words and actions and the surrounding events given to them by the author and be able to infer a character's thinking.

But not only do I want students to be able to infer those thoughts, I want them to be able to make sense of them. To make decisions and draw conclusions based on them.

But not only do I want students to make sense of those thoughts, I want them to be able to then explain it all. To verbalize it. Even to write it.

Whoa.

That's a lot.

But by slowing down the process of inferring and making sense of a character's thoughts (you know, Matrix slow-mo)--breaking it down, talking it out, recording it on paper--students begin to do it more naturally when they read.

So what?

What's the big deal? Why do I want students to be able to do all of this? Three reasons: When we become adept at thinking about what a character is thinking,

- we understand the character better and more deeply. We understand the choices and actions he/she makes, and can even better predict future choices and actions from that character.

- we connect to the character. We get to know him/her and the similarities to our own life. We can identify with, relate to, even learn from that character.

- we really hit some Common Core standards full on in the face. (Check CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.3.3, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.4.3, and CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.5.2 and 5.3.)

Enter, the thought bubble.

I love using a thought bubble because it gives students a concrete starting point for something that's not very concrete. And it becomes an anchor symbol that helps trigger the thinking about a character's thinking.

Before we get too far into a character's thoughts, it's really important to first show students how to slow down and explain their own thoughts.

via GIPHY

To practice recording students' own thinking, with lots of elaboration and details, try this preliminary activity:

Have students get out a notebook and pencil and prepare a large, empty thought bubble on their page. It should fill most of the page. Make sure you have one on the board, too.

Then go behind your desk and without students seeing, put something small, like a stapler or a glue bottle, in your hand and then hide it by draping a towel over it. Bring the covered item to the front of the room and dramatically explain to students that you have a surprise addition for the classroom. Jiggle the item slightly, as if it moved on its own, and then whisper-scold it to stay still.

Then go behind your desk and without students seeing, put something small, like a stapler or a glue bottle, in your hand and then hide it by draping a towel over it. Bring the covered item to the front of the room and dramatically explain to students that you have a surprise addition for the classroom. Jiggle the item slightly, as if it moved on its own, and then whisper-scold it to stay still.

Then go behind your desk and without students seeing, put something small, like a stapler or a glue bottle, in your hand and then hide it by draping a towel over it. Bring the covered item to the front of the room and dramatically explain to students that you have a surprise addition for the classroom. Jiggle the item slightly, as if it moved on its own, and then whisper-scold it to stay still.

Then go behind your desk and without students seeing, put something small, like a stapler or a glue bottle, in your hand and then hide it by draping a towel over it. Bring the covered item to the front of the room and dramatically explain to students that you have a surprise addition for the classroom. Jiggle the item slightly, as if it moved on its own, and then whisper-scold it to stay still.

Then, without revealing what the item is, say something like, "Let's pause right there for a moment, boys and girls. I want you to write down what you are thinking. What thoughts went through your mind when I brought this thing out? Write inside your thought bubble. Be honest, and be as detailed as you can."

After a few minutes, have a few students share their writing. (All the while, you are holding the covered item in your hand.) As each student shares, prod him/her and the class with questions to help them see opportunities for further elaboration.

Maybe a students writes, "I'm wondering what is under the towel," but after some prompting it could turn into, "My teacher just brought up something in her hand but it's covered with a towel. I'm wondering what is under the towel. Is this a joke? It looks like it just moved a little bit, so maybe it's alive. But Mrs. T. hates critters, so why in the world would she be holding something alive? I think she's just messing with us. But why is she messing with us? And even if it's not alive, I still would like to know what she is holding. Maybe it's a rock. Maybe we're going to do a unit on rocks."

Finally, reveal the item to students. "Don't you love it, boys and girls?" Egg them on a bit, and then stop them again. "Okay boys and girls, I want you to draw another thought bubble, and write down your thinking again. I want you to try to be even more detailed than before."

Give students a couple of minutes to write. As they work, turn to the board and write the words, "If I were you..." outside the thought bubble you drew and record a model example. Maybe something like, "When Mrs. T. took the towel off of the stapler, I was outraged! How could she think we'd enjoy this 'new addition' to our classroom? But then I calmed down a bit and realized she was probably doing all of this just to give us something to write our thinking about. But still, why couldn't she have done it with a gerbil or a frog or something? Like a new class pet. Would that have been so hard?! Oh dear, the outrage is returning!"

Before sharing with the class this time, have students pair up and read their thought bubbles to each other, comparing them and making suggestions on how to elaborate even more.

* * *

In your next lesson, transition to the thoughts of a character in a story. Refer to the elaborate thinking students recorded of their own and how they'll now apply this technique to explain a character's thinking.

Prepare a large thought bubble to model with a picture book. You can download a copy of the thought bubble you see in the images below by clicking HERE.

Some of my favorite books to use with this lesson are: The Old Woman Who Named Things, by Cynthia Rylant, The Gardener, by Sarah Stewart, any Henry and Mudge book (yes, even for upper elementary), Some Birthday! by Patricia Polacco, and Owl Moon, by Jane Yolen.

Gather students with their notebooks and pencils. Read aloud a portion of the story, and then pause at a certain point to record a character's thoughts in your thought bubble. As you write, point out evidence from the story, both from text and illustrations, that helped you infer the character's thoughts. (Which sort of means you're thinking about your thinking about the character's thinking. Whoa. Never mind, don't think about that.)

Continue reading. Then pause at another point and have students draw a thought bubble in their notebook and record what the character is thinking. As students write, erase your own thought bubble and fill it in with the character's new thinking. Then have a brief discussion with students about what they wrote and what you wrote.

* * *

When students get used to thinking about and recording a character's thoughts in detail, it's a good time to begin transitioning into doing it more naturally. As a stepping stone, have students record "thought bubble thoughts" on sticky notes.

If you do a class novel read aloud, use it to model for students how to find an important moment to pause, and how to record notes about what the character is thinking. Show students that since the sticky note is small, we have to be more succinct in how we write, maybe in a "jot it down" notes-style rather than complete sentences, but be clear that the thinking stays just as intense.

After modeling a sticky-note-thought-bubble with your novel read aloud, give all students a sticky note. Continue reading and choose a new spot to pause for students to practice for themselves. Discuss the sticky notes or collect them for a quick formative assessment check.

Choosing a common spot in the book for all students will help you assess how each student is progressing. Don't forget that having students discuss their inferences about a character's thinking can be just as meaningful as making the inferences.

It's also really interesting to use the thought bubbles to infer the thinking of a supporting character, not just the main character. Particularly with a book written in first-person, where the main character gives much of his/her thinking just by narrating the story, try changing students' perspectives and digging into the thoughts of one of the other characters in a scene.

Eventually, have students practice recording sticky-note-thought-bubbles with self-selected books they are reading in class. Keep the large laminated thought bubble handy to use with future texts and to be a reminder to students as they read on their own.

Ah, thought bubbles. They are such simple little things, but with the right guidance and modeling, they can be the jumping off point for some seriously deep and rewarding reading work.

Be sure to read my post about the Thought Bubble's more outspoken cousin, the Speech Bubble. You can read it here.

After modeling a sticky-note-thought-bubble with your novel read aloud, give all students a sticky note. Continue reading and choose a new spot to pause for students to practice for themselves. Discuss the sticky notes or collect them for a quick formative assessment check.

Choosing a common spot in the book for all students will help you assess how each student is progressing. Don't forget that having students discuss their inferences about a character's thinking can be just as meaningful as making the inferences.

It's also really interesting to use the thought bubbles to infer the thinking of a supporting character, not just the main character. Particularly with a book written in first-person, where the main character gives much of his/her thinking just by narrating the story, try changing students' perspectives and digging into the thoughts of one of the other characters in a scene.

Eventually, have students practice recording sticky-note-thought-bubbles with self-selected books they are reading in class. Keep the large laminated thought bubble handy to use with future texts and to be a reminder to students as they read on their own.

* * *

Ah, thought bubbles. They are such simple little things, but with the right guidance and modeling, they can be the jumping off point for some seriously deep and rewarding reading work.

Be sure to read my post about the Thought Bubble's more outspoken cousin, the Speech Bubble. You can read it here.